By Suzanne Seryck, Master Gardener

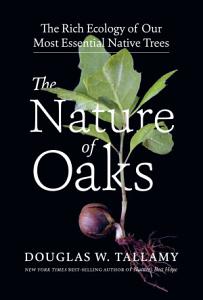

Like a lot of other gardeners during this time of COVID, I have taken advantage of the many, many gardening presentations, seminars, talks, and webinars that have all been available online–not to mention catching up on my reading. The two books that I am currently reading are both by Douglas Tallamy and have been recommended numerous times. They are ‘Bringing Nature Home’ and ‘Nature’s Best Hope’. Both are packed full of facts and figures; the first one providing a list of recommended native plants as well as basic information regarding the insects that are eaten by bird and wildlife. The second book, which is one of the main reasons why I like it so much actually has a plan (or approach as the book calls it) for turning our home gardens into wildlife habitats and extending that approach to create corridors preserving our native wildlife.

What I have noticed among the many presentations, seminars, etc. is the focus on native plants, native wildlife preservation, sustainable and organic gardening and environmental gardening. I am definitely all in favour of this shift; in fact I believe that this has been too long coming. We, as a whole, are definitely a little late to the table. Now this is just my personal opinion but I feel that as a nation, as a people, we do seem to be forever running behind a problem trying to come up with solutions only when the situation becomes critical!

I have to admit that I am as much at fault as the next person. My garden is only approximately 40% native plants, the rest being ornamental. Although if you count bulbs and annuals, that figure could drop down to about 30%.

But do not panic just yet, Douglas Tallamy does not recommend that we ‘adopt a slash and burn policy towards the aliens that are now in your garden’, thank goodness for that. What he does suggest is two-fold, if an alien plant dies replace it with a native plant that has the same characteristics, and two, create new beds with native plants if you have space and if not, dig up some of your lawn.

So here is my dilemma, and guilt. I have no more space to expand and only a very narrow patch of lawn in the back garden for my husband, dogs and future grandchildren. So I either have to wait for something to die, which is not happening fast enough to outweigh my guilt, or dig up a plant replacing it with a native. This is not quite as easy as you think. I have walked around my garden a number of times looking for plants to give away to plant sales or neighbours. The problem is the less plants you have the more each plant tends to have its own story, your mother or good friend gave it to you, you’ve inherited it from someone you care about, the plant reminds you of a certain time, the list and stories go on.

Photo of backyard in author’s garden showing on the left the narrow strip of lawn

One of my favourite native plants is culver’s root. It always and consistently has the most insect activity of any plant in the garden. I already have two. But would I want to dig up the rose bush that my mother bought me because coincidentally it has the same name as my grandmother and replace it with a third culver’s root?

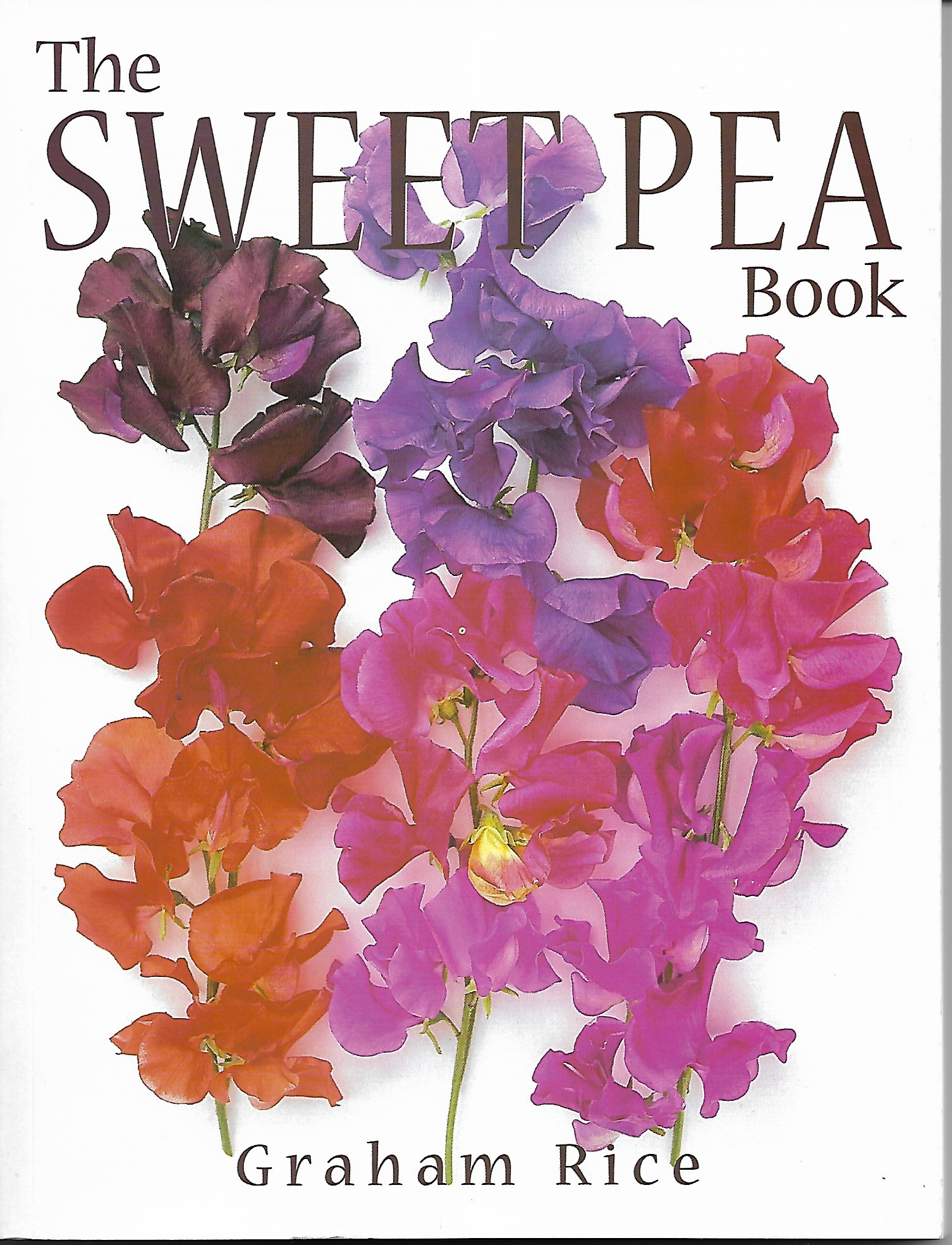

What about ironweed? I love this tall, stately plant covered in late summer with purple flowers. Again I already have two, but would I want to dig up the delphinium that a neighbour gave me 15 years ago, that had apparently been growing in her yard for 30 years prior to that and replace with an ironweed?

Picture of Ironweed in author’s backyard

What about all the daylilies I have spent years collecting, each one unique and individual, or the peonies I bought from my last garden, one in each colour? Now, I understand that maybe not all of my ornamentals have the same level of memories, and that, yes, they would be going to good homes. But it is a difficult decision, I want to increase the natives in my garden, I want to do what is right and sustainable, and I want to increase the wildlife in my garden. I have even given talks myself encouraging gardeners to add at least one native plant to their garden each year. But do I really have time to wait; my guilt levels and motivation levels want me to act now, to take a stand, to encourage by action.

As Douglas Tallamy concludes: ‘Our success is up to each one of us individually. We can each make a measurable difference almost immediately by planting a native nearby. As gardeners and stewards of our land, we have never been so empowered – and the ecological stakes have never been so high.’

This book is, without a doubt, one of my favourite go-to gardening books! The new revised third edition of Lorraine Johnson’s book, 100 Easy-to-Grow Native Plants for Canadian Gardens, is a testament to Lorraine’s expertise. She writes in the forward that “one of the greatest satisfactions of growing native plants is that you are supporting a complex web of ecological relationships that are the basis of a healthy, resilient ecosystem.” Lorraine Johnson is the former president of the North American Native Plant Society and the author of numerous other books. She lives in Toronto.

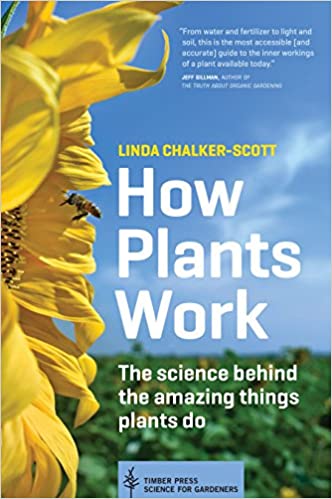

This book is, without a doubt, one of my favourite go-to gardening books! The new revised third edition of Lorraine Johnson’s book, 100 Easy-to-Grow Native Plants for Canadian Gardens, is a testament to Lorraine’s expertise. She writes in the forward that “one of the greatest satisfactions of growing native plants is that you are supporting a complex web of ecological relationships that are the basis of a healthy, resilient ecosystem.” Lorraine Johnson is the former president of the North American Native Plant Society and the author of numerous other books. She lives in Toronto. The photos by Andrew Layerle, along with detailed descriptions of the plants, make this book most helpful when trying to decide what native plants you would like to incorporate into your garden. I think many of us can relate to her point that “gardeners tend to be voyeuristic creatures and plant lists are our chaste form of porn”! We all crave the perfect plant and often browse through books over the winter months with dreams of starting a new garden and we wait patiently for the spring weather that allows us to once again get our hands dirty.

The photos by Andrew Layerle, along with detailed descriptions of the plants, make this book most helpful when trying to decide what native plants you would like to incorporate into your garden. I think many of us can relate to her point that “gardeners tend to be voyeuristic creatures and plant lists are our chaste form of porn”! We all crave the perfect plant and often browse through books over the winter months with dreams of starting a new garden and we wait patiently for the spring weather that allows us to once again get our hands dirty. The plants are divided into a number of different categories and Lorraine does a good job at listing the common name (although she warns there are sometimes many), the botanical name, the height, blooming period, exposure, moisture, habitat and range. She gives a good description, the maintenance and requirements, along with suggestions on propagation and good companions. I love that she also mentions the wildlife benefits of each plant.

The plants are divided into a number of different categories and Lorraine does a good job at listing the common name (although she warns there are sometimes many), the botanical name, the height, blooming period, exposure, moisture, habitat and range. She gives a good description, the maintenance and requirements, along with suggestions on propagation and good companions. I love that she also mentions the wildlife benefits of each plant. Lorraine has also included Quick-Reference Charts at the back of the book that separate the plants by region as well as specific conditions, such as acidic soil, water requirements, etc. She has lists of plants suitable to prairie habitat, drought-tolerant plants, plants for moist areas, and plants that attract butterflies and other pollinators.

Lorraine has also included Quick-Reference Charts at the back of the book that separate the plants by region as well as specific conditions, such as acidic soil, water requirements, etc. She has lists of plants suitable to prairie habitat, drought-tolerant plants, plants for moist areas, and plants that attract butterflies and other pollinators.