by Emma Murphy, Master Gardener

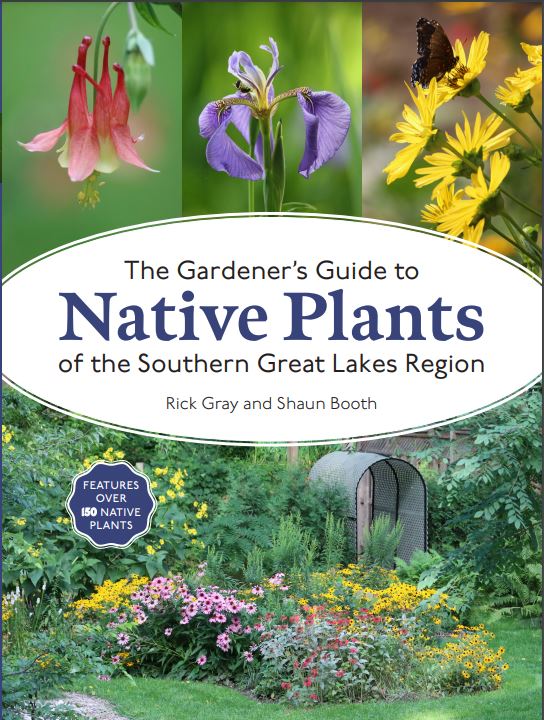

Wow. What a pleasure to finally see this book in print. Written by two very knowledgeable Ontario gardeners — Rick Gray and Shaun Booth — this is the native plant gardening resource I wish I had more than 5 years ago when I started incorporating native plants in my garden.

Focused specifically on the Southern Great Lakes Region, it’s an all-in-one, easy to use resource for those interested in plants that not only look wonderful but fulfill a critical role in our gardens in supporting wildlife, birds, and pollinators like butterflies, moths, bees, and insects.

It reminds me of an encyclopedia, with a full page spread on each native plant (and there’s over 150!). It’s not surprising to me that’s it’s already #4 on the Globe & Mail’s bestseller list.

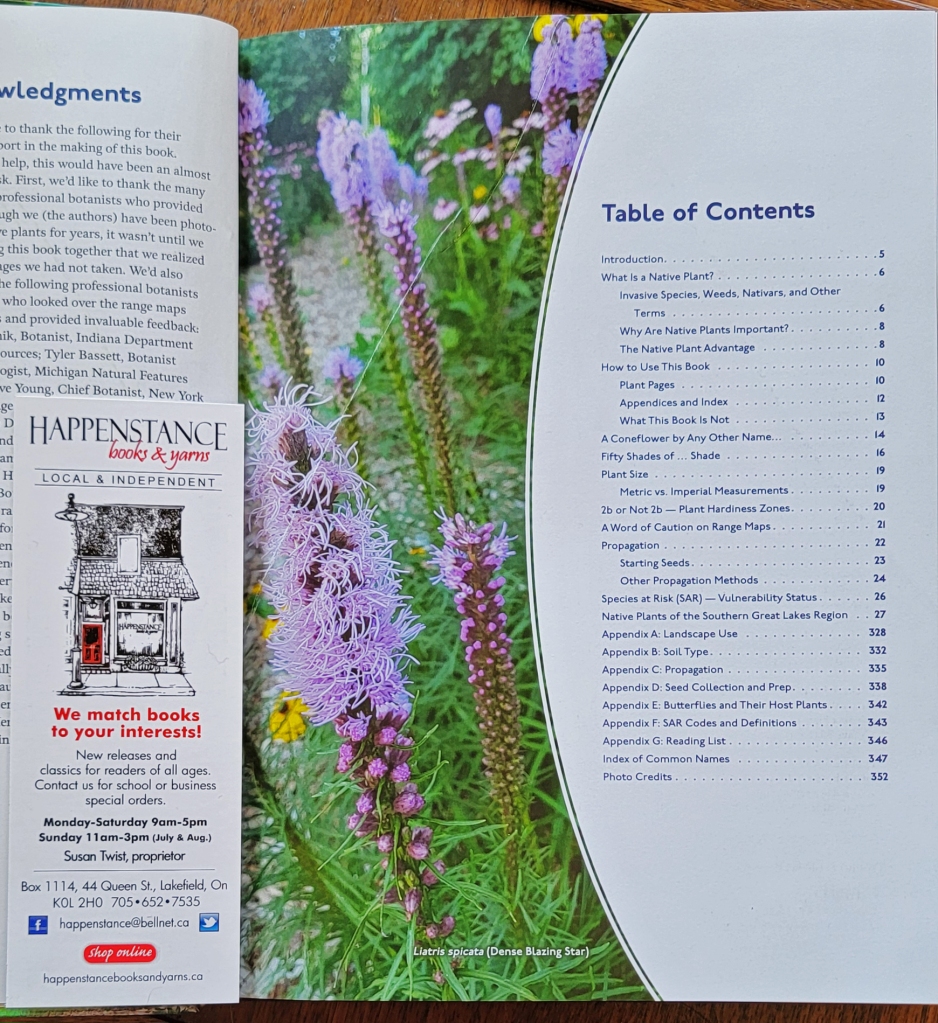

The book is visually designed to make it easy to see key information at a glance, using quick guide key icons and two colour-coded bars providing exposure/light and moisture requirements. We’ve been blessed with several excellent native plant books in the past few years, but I appreciated several unique elements I hadn’t seen before – numerous appendices (matching soil types, seed collection and preparation, propagation, and butterflies and their host plants), as well as each plant’s Ontario’s Species at Risk status.

You’ll understand what each plant needs to thrive, how big they will get, and how to make more plants to share with your friends!

As a Peterborough Master Gardener I have long been engaged in two Facebook groups – the Ontario Native Plant Gardening group (started by Shaun) and the Master Gardeners of Ontario group (where I am an admin and moderator). I remember clearly in May 2023 Rick trying to gauge interest from members on their proposed native plant book, and the incredibly positive response that they received. So full disclosure – I knew I was going to love this book before it was ever published.

The authors explain why the plants are organized by botanical/Latin name, which is important because common names can vary by region. However, if you only know the common name you can always search using the alphabetical index at the back of the book.

Essentially, each entry is a ‘checklist in a page’ on what you need to grow the plant. There are lots of photos (whole plant, leaves, flowers, fruiting bodies), a detailed description, easy to see symbols (the Quick Guide), information on the USDA Hardiness Zone, lifespan, propagation, and wildlife/pollinator value.

Skill levels are also mentioned but don’t be alarmed – most are listed as beginner, but there are certainly a few native plants that are a bit more challenging to grow and propagate.

I appreciate that in the introductory chapters the authors clearly explain things such as:

- What is a native plant?

- Aggressive vs invasive

- Origin of the term weed

- Nativar vs cultivar

- Value of native plants

The authors clearly have a good sense of humour – there are pages titled “How to use this book”, “A coneflower by any other name”, “Fifty shades of…shade” and my favourite “2b or not 2b” (on the rationale for using USDA Hardiness zones). I loved the section on propagation and codes as I’m actively trying to grow more native plant material in my area.

I have to say that as a seasoned gardener I was surprised to see Echinacea pallida (pale purple coneflower) is not in the book (not native to most of this region but often sold as a native apparently) and Agastache foeniculum (Anise hyssop) is one that is included specifically because it is non-native to Ontario (it’s a western prairie plant). Oops! I have both in my garden north of Peterborough.

Was anything missing? Technically no, as the authors were clear that this was not a garden design book. Perhaps after putting out Vol. 2 (the other 150+ plants I know they wanted to include), they’ll consider something on understanding planting density and creating root competition, which I am learning is different to conventional perennials, and good plant pairings (which native plants support others).

One quick comment I will add is that native plants are wonderful once they are established, so you may need to do a bit of watering that first year, but after that they need no watering or fertilizing.

If you’re interested in hearing about how this book came to be check out Rick’s Native Plant Gardener website.

This book is perfect for reading at home (my husband gave me a quick quiz contest this afternoon on the Latin names) or taking with you to your local nursery as you search for native plants to add to your garden. Having trouble finding these plants? The Halton Region Master Gardeners maintain a dynamic map listing native plant nurseries around the province. Check it out!

The bottom line – a wonderful addition to my garden library, and to anyone interested in incorporating more native plants in their Ontario gardens.

__________________________________________________________________________

The Gardener’s Guide to Native Plants of the Southern Great Lakes Region

By Rick Gray and Shaun Booth

Publisher: Firefly Books, 2024

Paperback: 352 pages ISBN-10: 0-2281-0460-2

Price: C$45.00; available through local booksellers and larger book companies

About the Authors

Rick Gray (The Native Plant Gardener) has more than 300 species of native plants in his garden in southwestern Ontario and provides native plant garden design services.

Shaun Booth runs In Our Nature, an ecological garden design business, and launched the Ontario Native Plant Gardening group on Facebook.

Want More Information?

Many wonderful books on native plant gardening and naturalization have been published in the past few years – anything by Lorraine Johnson is a great complement to this book, and I love Piet Oudolf’s work (although he doesn’t always use native plants).

Dr Linda Chalker-Scott (and the Garden Professors blog on Facebook) is a great source of good, solid scientific information on gardeners keen to avoid the misinformation often seen on social media.

And if you’re on Facebook, please follow both the Master Gardeners of Ontario and Ontario Native Plant Gardening groups.

Other Native Plant Blog Posts By Me

A Few of My Favourite Native Plants

Native Ontario Goldenrods for Your Garden