By Silvia Strobl, Master Gardener in Training

True confession: In 30 years of growing a vegetable garden I’ve never made a planting plan. I only make a sketch noting what was grown in each planting bed so that I rotate crops over a 3-year cycle to minimize pest build-up.

Recently, I was introduced to the idea of making a planting plan to both optimize garden space for vegetables to be grown and ensure timely harvests and succession sowing/planting–of particular importance in our short growing season! Now is a great time to plan. To illustrate how, here are the steps to grow 6 crops in a hypothetical garden plot 12 feet x 12 feet in size.

Step 1: Identify the Average Date of Last Spring Frost and Average Date of First Fall Frost for your garden location. By consulting this Ontario map, we see that Peterborough is in Zone E with a May 17 last frost and a September 26 first frost, giving a 19-week or 133-day growing season.

Step 2: Identify the vegetables you want to grow, and note the weeks to maturity (i.e., estimated time before you can harvest edible vegetables) on the seed packet. Decide whether you will direct sow or plant seedling transplants that have either been purchased or sown indoors. In short growing seasons, transplants can give you a head start and are recommended for crops that take more than 100 days to mature.

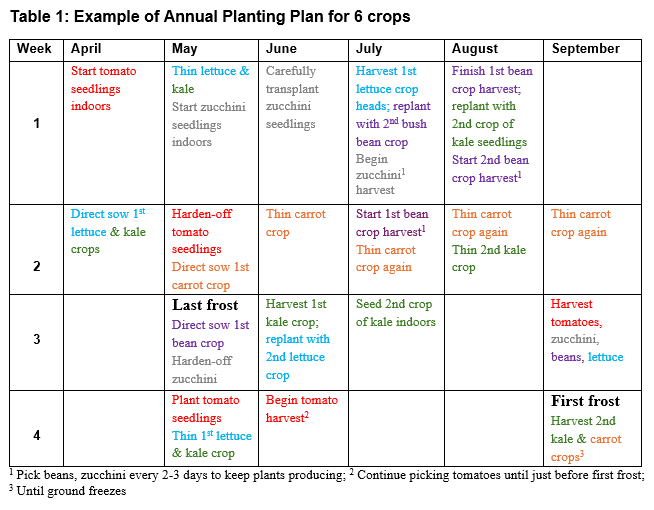

Step 3: Make a schedule either on paper or in digital format, by creating a table with the months of the growing season as columns and the 4 weeks in each month as rows (see Table 1 or this more detailed worksheet). Identify in which weeks the following events for each crop will occur:

- Direct sowing of cool season crops like lettuce, spinach, kale and snow peas (second week of April in Peterborough)

- Either direct sowing or planting of seedling transplants of warm season crops like carrots, beans, squashes, melons, tomatoes (third week of May, or later)

- Count the weeks to maturity and identify when harvest will occur for each crop

- Identify if there will be enough weeks in the growing season to sow or plant the space with a second crop of after the first crop is harvested

- If you can sow or plant a second crop, add these actions to the schedule, ensure the second crop in any planting bed is from another vegetable family

- Finally, add in other key dates, like when seedling transplants need to be sown indoors in spring and hardened off, or in mid-summer (for a second crop), if growing these yourself

Table 1 shows a schedule for 6 crops and identifies that the growing season in this hypothetical garden can accommodate harvests of two kale, lettuce, and bush bean crops, and one carrot crop.

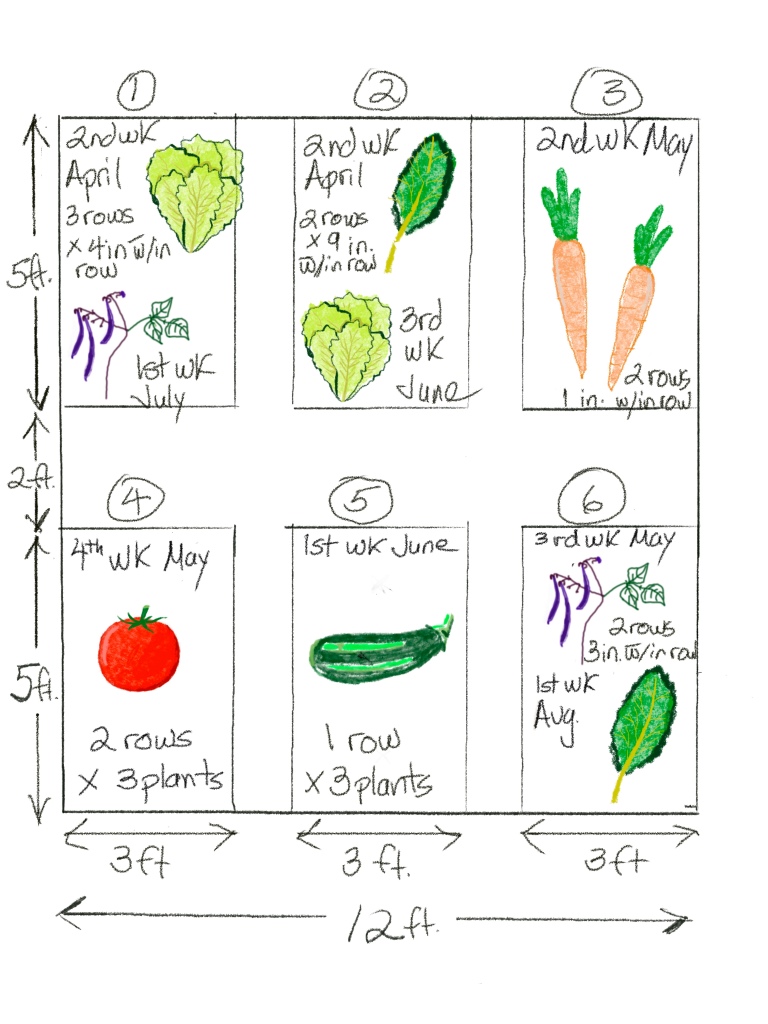

Step 4: Identify where each crop will be planted by sketching a map to approximate scale of your planting beds. Refer to the recommended spacing on the seed packet, to identify how many plants will be sown or planted. Refer to notes about the past 2 years of planting to ensure you don’t grow the same crop in the same location as the years before.

Figure 1 shows the 12-foot square hypothetical garden divided into 6 beds, each 3 feet by 5 feet. We immediately notice that nothing is planted in beds 4 and 5 until the last week of May and the first week of June, respectively. Could radishes (3 to 5 weeks to maturity) and spinach (5 to 6 weeks) have been planted in mid-April in beds 4 and 5, respectively, and mostly harvested just before planting the small tomato and zucchini seedlings?

You will likely grow more than 6 vegetable crops. For example, you could plant seedlings of a short-season broccoli instead of kale crop #1 and snow peas instead of bush bean crop #1. But, if you follow these steps to make a planting plan almost every inch of your garden space will be used from as soon as cool-season crops can be sown to when crops such as kale, cabbages, carrots, and parsnips are touched by the first frosts that concentrate sugar content and improve their taste. You might also include annual flowers like marigolds, calendula and alyssum that not only add beauty to the vegetable garden but attract pollinators.

By recording yields in your garden over the years, the planting plan can be fine-tuned so that the number of plants of each crop grown is as much as your family can eat. Nobody wants to be overwhelmed by too many zucchinis!

It is a bit of work upfront to make a planting plan, but it will save time over the growing season because you will know exactly when and where each crop will be planted, at what spacing, and which crop will succeed the one just harvested. You will also save money by only buying seeds for crops that will be grown!

I am going to try this for my vegetable garden this year, how about you?

For more info on growing veggies in Ontario check here. Also check the Peterborough & Area Master Gardeners resources page here for fact sheets on growing lots of different kinds of vegetables.

Related:

ARE YOU IN THE ZONE?

METHODS OF GROWING FRUITS AND VEGETABLES EFFICIENTLY IN SMALL SPACES

HOW TO MAKE YOUR VEGETABLE GARDEN BEAUTIFUL

GROWING VEGETABLES

PREPARING YOUR GARDEN BEDS FOR PLANTING VEGETABLES AND ANNUALS