Laura Gardner, Master Gardener

Ancient Seeds

Back in the 1890s, the mouth of the Don River in Toronto was filled in to make way for industry—known as the Port Lands. This changed the landscape and the plants that used to grow there “disappeared.” In 2021 while the site was being ecologically restored as part of the Port Lands Flood Protection Project, workers discovered some unusual plants that had sprouted shortly after seven metres of soil had been excavated. They were thought to be different than the usual species seen at the site.[i] Researchers at the University of Toronto began working to identify the species of plants and seeds found.[ii] Some of the plants included Schoenoplectus (Bulrush), Typha (Cattail), Salix exigua (Coyote Willow), Equisetum (Horsetail), as well as mosses and liverworts. Research is still ongoing as they seek to verify whether these plants came from an ancient seed bank. Through carbon dating, the research team was able to determine that some of the seeds from soil samples were between 150-400 years old! So far, most of the seeds that have been identified were from the Cyperaceae (Sedge) family with the majority in the Carex (True Sedges) genus followed by Schoenoplectus (Bulrushes), Sparganium (Bur-Reed) and Typha (Cattail).[iii] This is all very exciting because it shows that while some urban environments may be drastically altered, they are not necessarily permanently altered, and we may be able to successfully restore such landscapes to their pre-industrialized states.

Seed Dispersal and Physical Dormancy

Most seeds are known to be “physiologically dormant.” This means that they have an internal inhibiting mechanism (“endogenous”) that requires exposure to certain conditions to break dormancy (e.g. light, temperature, etc.).[iv] “Physically dormant” seeds have an external inhibiting mechanism (“exogenous”)—a hard coating that inhibits germination unless it becomes permeable–allowing water to enter, and then germination is initiated.[v] Some years ago, I planted a Zebrina Hollyhock Mallow (Malva sylvestris) in my garden. It is considered a biennial or a short-lived perennial. It bloomed but didn’t come back the following year and no new plants emerged from any possible dispersed seeds. It was not until about five years later that two plants emerged—about four metres away from the original plant site. These seeds are quite hard and require some form of natural scarification to break their seed coats. Scarification can occur through fluctuations in temperature, damage by gardening tools, damage by microorganisms, fungi, or animals; or transit through animals’ digestive tracts.”[vi] Myrmecochory could possibly explain the transfer of the seed from one location to another as seeds in the Malva family are frequently targeted by ants.[vii] In myrmecochory, ants transport the seeds and then remove and eat a nutritious coating from the seeds called the elaiosome. Sometimes when the elaiosome is removed, the seed coat becomes thinner, and this enables water to enter. However, Baskin and Baskin suggest that removal of the elaiosome by ants on seeds like this may not influence the seed’s ability to imbibe moisture.[viii]

Photo Credit

“Malva sylvestris sl27” by Stefan.lefnaer is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Recalcitrant[ix] or Hydrophilic[x] Seeds

When I think about some of the plants I grew from seed last year, I recall one species that did not have good germination—Geranium maculatum (Wild Geranium). There are different causes for poor germination, but one possibility is that the seed was not fresh enough or that their moisture content was not sufficiently retained. I learned that this species is somewhat recalcitrant or hydrophilic. These types of seeds are sensitive to drying and as time progresses, the percentage of seed death increases. William Cullina, in Wildflowers: A Guide to Growing and Propagating Native Flowers of North America, recommends sowing Geranium maculatum immediately upon harvest of the seeds in the summer. However, germination may be successful with seeds stored in plastic for 4-6 months—perhaps indicating this species inclination towards being partially recalcitrant.[xi] According to Dr. Norman Deno in Seed Germination Theory and Practice, Geranium maculatum is best sown in the summer from fresh seed and then is exposed to winter temperatures before germinating in the spring. Seeds are mostly dead when kept in dry storage for more than 6 months.[xii] One of the lessons learned here is to research the germination requirements thoroughly as well as inquire about the storage conditions/age of the seed before obtaining seed of a recalcitrant species from a supplier.

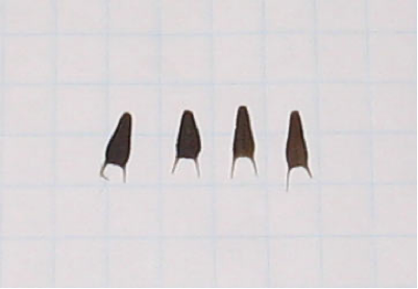

Heteromorphic or Dimorphic Seeds

Although considered a composite species, Bidens frondosa (Devil’s Beggarticks), usually lacks ray flowers and only has disk flowers. As a result, they are less attractive to pollinators than the other Bidens species.[xiii] It also has a weedier reputation. Being an annual, each plant can produce around 1,200 seeds that are viable for 3-5 years. The seed is a two-barbed achene that can stick to clothing and pet fur. Interestingly, the achenes are known to be heteromorphic or dimorphic in nature—there are two different kinds. Those produced on the periphery are black, thicker, and are less dormant than the ones produced in the middle. Those in the middle are brown, elongated, and are more dormant than the others. This is an example of how a plant has a particular way of increasing its rate of reproductive survival—the less dormant achenes fall close to the mother plant and germinate the following year while the ones that are more dormant are carried by animals (“epizoochory’) or by wind (“anemochory’) to germinate at different times in new environments.[xiv] These seed features help explain the resiliency and ability of this species to proliferate.

Photo Credit

Richard Frantz Jr., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/ef/Beggarsliceseeds.jpg

Photo Credit

Tephrosia virginiana (Goat’s Rue) seeds germinating

Resources

[i] Waterfront Toronto. 100-Year-Old Seeds. Online: https://www.waterfrontoronto.ca/news/100-year-old-seeds

[ii] University of Toronto. In the Media: Shelby Riskin discusses her research on ancient seeds found at the Don River. Online: https://eeb.utoronto.ca/2023/10/in-the-media-shelby-riskin-discusses-her-research-on-ancient-seeds-found-at-the-don-river/

[iii] Riskin, Shelby. Email communication (December 2023).

[iv] Willis, C.G., Baskin, C.C., Baskin, J.M., Auld, J.R., Venable, D.L., Cavender-Bares, J., Donohue, K., Rubio de Casas, R. and (2014), The evolution of seed dormancy: environmental cues, evolutionary hubs, and diversification of the seed plants. New Phytol, 203. p. 301. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12782

[v] Baskin, Carol C. and Jerry M. Baskin. Seeds: Ecology, Biogreography, and Evolution of Dormancy and Germination. 2nd Edition. 2014. p. 72.

[vi] Ansari, O., Gherekhloo, J., Kamkar, B. and Ghaderi-Far, F. (2016), Seed Sci. & Technol., 44, 3, p. 11. http://doi.org/10.15258/sst.2016.44.3.05

[vii] Baskin and Baskin, p. 681.

[viii] Ibid., p. 682.

[ix] Ibid., p. 8.

[x] Ontario Rock Garden and Hardy Plant Society. Hydrophilic Seeds will not Survive Dessication. Online: https://onrockgarden.com/images/Seedex/ABOUT_HYDROPHILIC_SEEDS.pdf

[xi] Cullina, William. Wildflowers: A Guide to Growing and Propagating Native Flowers of North America. 2000. p. 254.

[xii] Deno, Norman C. Seed Germination Theory and Practice. 2nd Edition. 1993. p. 148.

[xiii] Hilty, John. Illinois Wild Flowers. Online: https://www.illinoiswildflowers.info/wetland/plants/cm_beggarticks.htm

[xiv] Brändel, Markus. Dormancy and Germination of Heteromorphic Achenes of Bidens frondosa,Flora – Morphology, Distribution, Functional Ecology of Plants. Volume 199, Issue 3, 2004, pp. 228-233.