By Silvia Strobl, Master Gardener

Are you curious about the birds, insects, and other wildlife visiting your garden? iNaturalist (free iOS/Android app) lets you photograph organisms, get AI suggestions on identification, and submit observations that expert naturalists can verify and researchers can use. Knowing which organisms are using your garden both gives you a greater appreciation of its contribution to the local ecology and can help you support visiting wildlife’s needs. A few examples of how you can use iNaturalist follow.

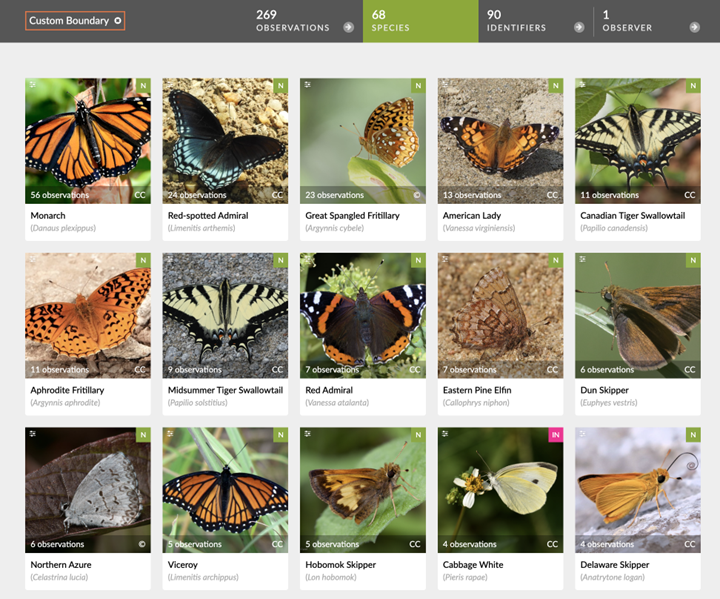

- You can easily generate a summary of observations in your garden in iNaturalist–in my case 68 species of butterflies and moths in my garden north of Peterborough since 2021.

- Two summers ago I found caterpillars eating my Snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus). iNaturalist identified them as Snowberry Clearwing Moth (Hemaris diffinis). After pupating, they overwinter in leaf litter — so leaving leaves under trees and shrubs can protect its pupae and that of many other butterflies and moths.

- You can use iNaturalist to learn which species use your garden and then plant their host plants (required to feed its caterpillars). In 2024 I recorded a rare Spicebush Swallowtail (Papilio troilus) visiting Bee Balm (Monarda didyma). Its hosts are Sassafras and Spicebush — plants of the Carolinian Forest ecoregion. Researchers using citizen science records over an 18-year period have already documented North American butterfly range changes towards cooler and wetter locations with climate warming (da Silva and Diamond 2024). The next spring, I planted 12 seedlings of Spicebush. Although planting native species from further south of your location is generally not recommended, small experiments can be informative.

I submitted the above 2 photos to iNaturalist. My observation was reviewed by one of Ontario’s foremost butterfly experts, Rick Cavasin, who verified it was actually a Spicebush Swallowtail. It is one of only a few observations to date of this butterfly in central Ontario.

- You could also use iNaturalist to identify a species you want to attract to your garden. I recently heard about a Brooklyn Bridge Park (New York City) gardener’s success in attracting the pollen specialist Spring Beauty Mining Bee (Andrena erigeniae) by planting hundreds of its host plant, Spring Beauty (Claytonia virginica), over several years. Twenty-five percent of eastern North America’s 770 native bumble bee species are pollen specialists that can only raise their larvae on pollen from either a group of closely-related plant families, a single genus, or, even just a single species (Fowler & Droege 2020).

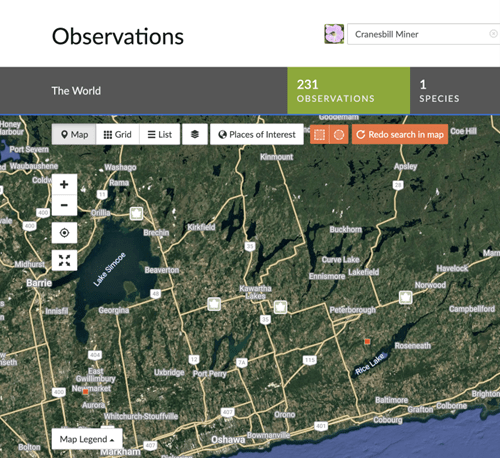

- I am winter sowing Wild Geranium (Geranium maculatum) to support spring pollinators and to try attracting the Cranesbill Miner (Andrena distans) another pollen specialist, but this may be challenging because there are no reports of this species north of Peterborough (see map below). The lack of records could be due to fewer iNaturalist observers in this location and gardeners’ casual contributions could provide a more complete picture of biodiversity from their gardens.

Getting Started with iNaturalist

I hope you are inspired to use this tool. You can download either the iOS (for an iPhone) or android version of iNaturalist from the App Store. This quick video shows you how to use iNaturalist while this one provides more details and shows how you can use data in iNaturalist to learn which species have been observed in your local area.

To Learn more about Ecological Gardening watch this TED Talk by Rebecca McMackin which has more than 450,000 views.

If you like butterflies, you may find this pocket guide to Ontario’s butterflies and moths by Rick Cavasin helpful.

Research Cited

da Silva, C. R. B., & Diamond, S. E. (2024). Local climate change velocities and evolutionary history explain multidirectional range shifts in a North American butterfly assemblage. Journal of Animal Ecology, 00, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.14132

Fowler, J. and S. Droegge. 2020. Pollen Specialist Bees of the Eastern United States. https://jarrodfowler.com/specialist_bees.html